In addition to the below, a History of the Bar exhibition is also available as a standalone presentation on Microsoft Sway. The exhibition focuses on pivotal legal figures and their role in the history of the Irish State.

A History of the Law Library and its Influence on the Independent Bar of Ireland

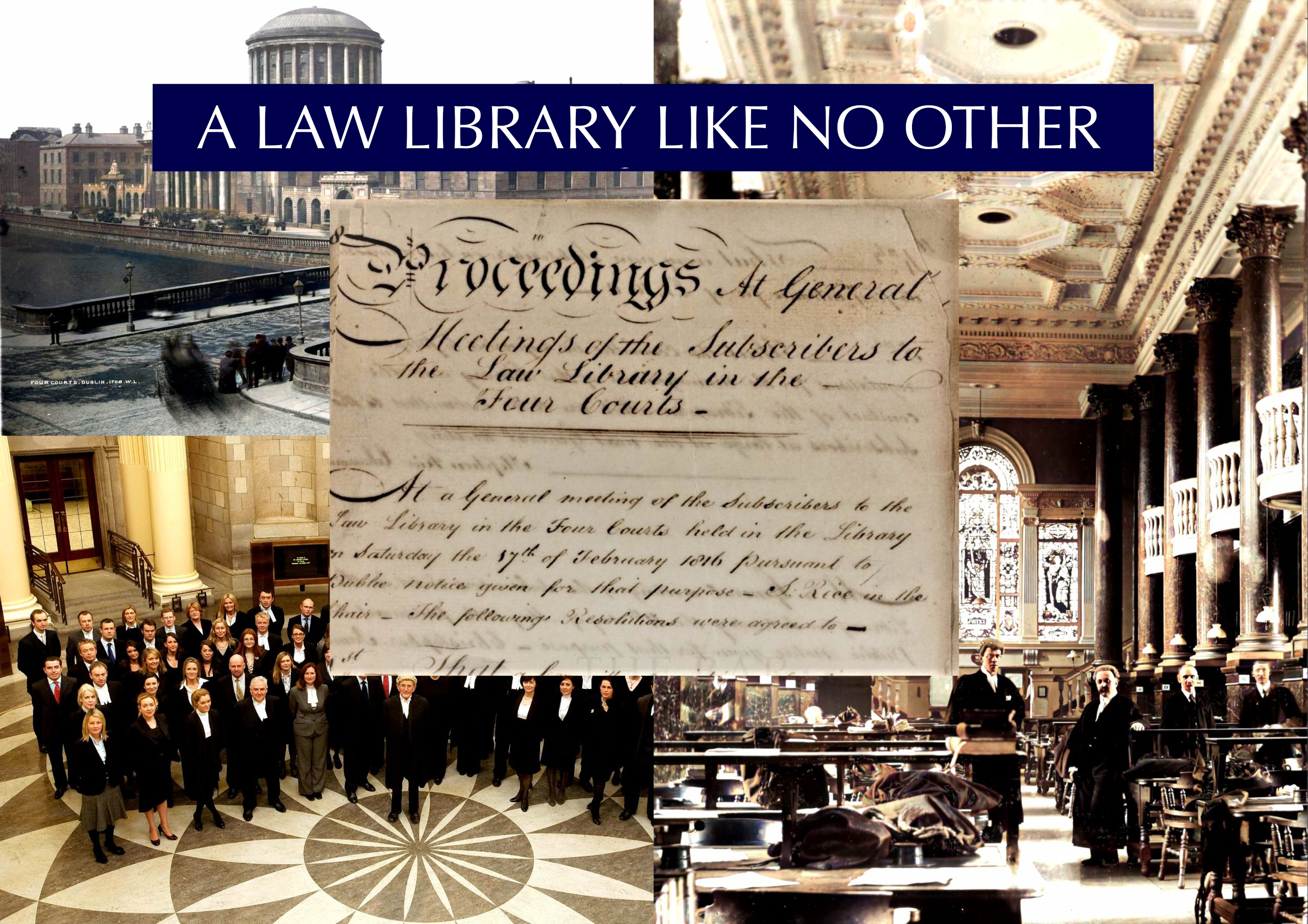

This exhibition tells the story of the Law Library and how it has helped to influence the development of the independent Bar that we see in Ireland today. Unlike their counterparts in England and Wales, barristers here never chose to enter into a chamber system, rather they preferred to remain a part of a greater institution. One of the reasons for its success can be attributed to the atmosphere of collegiality that has been nurtured over the centuries. As Judge Eugene Sheehy once remarked of a novice barrister, “When he joins the Law Library of the Four Courts he is a member of one of the best clubs in the world… the young counsel with the lily-white wig is made to feel that his call to the Bar has made him straightaway ‘a member of the house’ “.

Origins of the role of ‘Barrister’

The profession of barrister has been in existence in Ireland since the arrival of the Normans in the 12th century and with them the structures of the common law legal system. The common law system attached significance to judge-made law, with a decision in one case being legally binding on all subsequent cases of similar facts. Cases were contested in court in an adversarial manner, where good oratorial skills and a sharp intellect were required to win the day. In the early days it was common for those pleading before the courts to be known by a variety of terms and by the 17th century ‘counsellor’ was the most commonly used. The term ‘barrister’, though in existence since the 16th century, did not become generally used until the 19th century.

Those wishing to study the law and enter the legal profession had to attend at the Inns of Court in London in order to ensure a consistency in the knowledge and application of the law across England and Ireland. After much petitioning of the crown, in 1541 the Honorable Society of King’s Inns was established on the present site of the Four Courts. This meant that Irish lawyers could now achieve their training within Ireland with an obligation to keep terms in one of the Inns of Court in London. This requirement was, however, costly to Irish barristers and continued a contentious issue until it was abolished by the Barristers’ Admission (Ireland) Act 1885. Though ‘keeping terms’ had helped to ensure a close professional connection between Irish and English barristers there still emerged a distinctly Irish legal style, particularly during the 18th century.

The Irish Bar in the Eighteenth Century

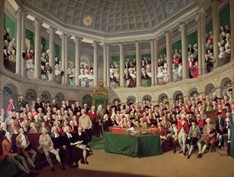

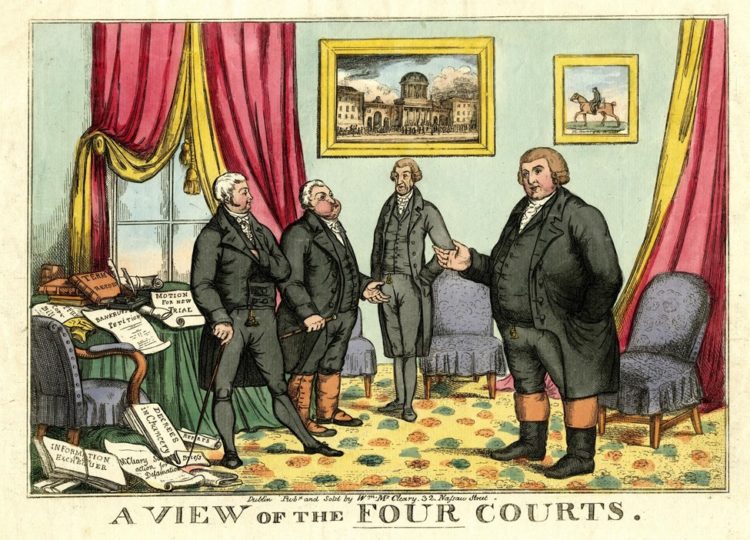

The courts were considered popular theatres of entertainment for spectators.

The centre of Irish law in the 18th century was the Four Courts in Christ Church Lane, a narrow street in Dublin’s Liberties. The courts had occupied a site adjacent to Christ Church Cathedral since the beginning of the 17th century and were always the scene of incredible activity, especially during sessions and market days. By 1796 the Four Courts had moved to Inns Quay, where James Gandon designed the neoclassical Four Courts building that is still in use today.

The courts were considered popular theatres of entertainment for spectators. Witnesses, defendants and barristers all had their groups of supporters who would cheer on their favourites, and court cases usually involved a noisy battle of wits, as insults were freely traded, and the winner was whoever was the sharpest. Barristers practised in Dublin as well as on circuit, with each of the provinces having its own circuit and barristers going ‘on circuit’ twice a year.

Some 711 barristers practised in Ireland in 1793, compared to only 604 for the whole of England and Wales. Many barristers had a social conscience and became involved in political radicalism. Before the Act of Union, barristers were actively involved in the Irish Parliament as it provided career opportunities to a profession that numbered more barristers than legal work. They also made their presence felt as leading politicians in the Irish House of Commons and the Houses of Parliament in London, where their oratory and vast experience of public speaking was a great advantage.

At the time of the opening of the new Four Courts in 1796 the legal profession was made up solely of men. Women were not allowed to enter the profession, indeed they had no legal status separate from their husbands under the legal doctrine of coverture and it would be another 125 years before women began to practise at the Bar in Ireland. Most barristers at the end of the 18th century were sons of landed gentlemen, Church of Ireland clergymen, judges, barristers, attorneys and physicians with some from the emerging commercial middle class. All but a handful were of the Protestant religion which was in large part due to a law that existed up to 1792 where barristers had to take a religious oath when being called that had been designed to exclude Catholics.

Regulation of the Bar

The 18th century witnessed the increasing regulation of barristers in Ireland. The Benchers of the Honorable Society of the King’s Inns essentially constituted its governing body. Originally they consisted of the Lord Chancellor of the day, the judges of the superior courts, some senior officers of these courts and all the senior members of the Bar including the Attorney-General, the Solicitor General and the three Serjeants. Following their call to the Bar a barrister was still under the jurisdiction of the Benchers and they had the power to censure or, as in some rare cases, disbar them.

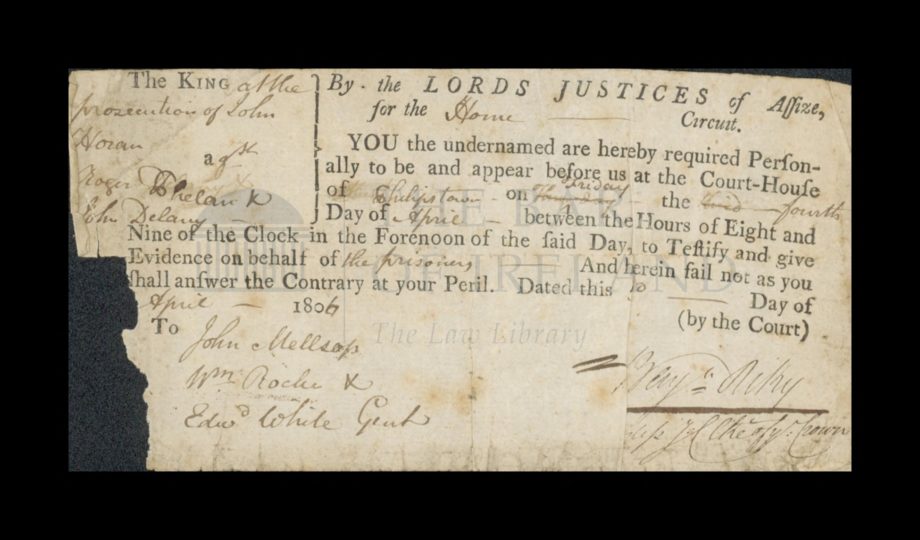

Image of a supoena from 1806 that was recovered from the streets outside the Four Courts after the mine explosion during the Civil War. ©Bar of Ireland Digital Archive

Wanting a greater supervision of candidates for the Bar in 1782 a statute regulating admission to the Irish Bar was passed stipulating that candidates must be registered on the books of the King’s Inns as a student for 5 years, or 3 years in the case of graduates in Law or Masters of Arts of the universities of Oxford or Cambridge. From 1783 it became a requirement that information about the parents of potential barristers be submitted, and from 1789 it was required that candidates be nominated or sponsored for admission by Benchers.

In May 1792, the Benchers considered draft Rules for the government of the profession that were rejected by the Bar at large in July of that year. In December 1793, however, a Committee of Benchers settled rules and orders for the regulation and better government of the Society which included requirements for all barristers, solicitors and bar students to be a member of the Society of King’s Inns.

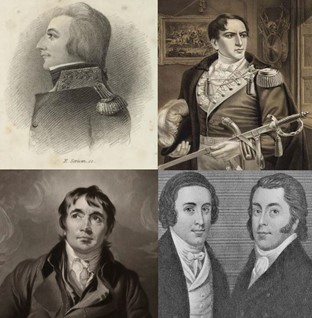

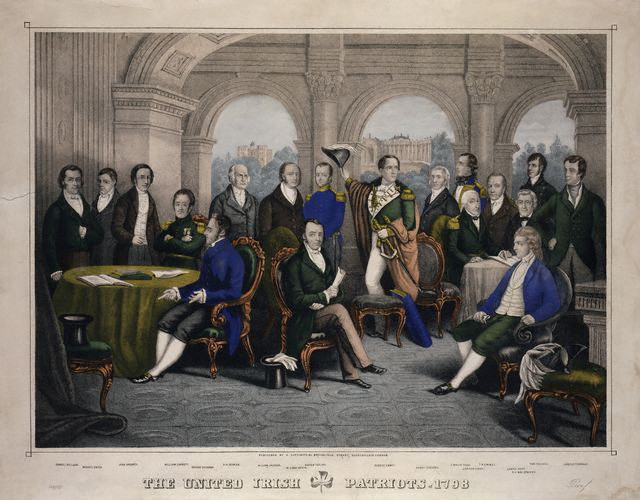

The Irish Bar and 1798

The 1798 Rebellion was a defining event for modern Irish republicanism and many of the key people involved were barristers. Influenced by the French Revolution of 1789 and disillusioned with the slow pace of reform in Ireland, some barristers believed that radical change was necessary, and they sought to break the connection between Britain and Ireland completely. By the 1790’s approximately 30 barristers were members of the Dublin Society of the United Irishmen and many of the key figures involved in the 1798 rebellion by the United Irishmen were barristers, not least Theobald Wolfe Tone.

After the rebellion was brutally suppressed by the Crown forces, twelve barristers were treasonably implicated in the rebellion, of which five were sentenced to death – Wolfe Tone, Sir Edward Crosbie, Beauchamp Bagenal Harvey and the brothers Henry and John Sheares.

Of the remaining seven, three (Thomas Addis Emmet, Arthur O’Connor and Roger O’Connor) spent the rest of the war as prisoners at Fort George on the east coast of Scotland; two, William Sampson and John Moore, were permitted to go to Portugal and into exile; one, James Joseph O’Donnell, escaped to America and the final one, Samuel Turner, was at all material times abroad. However, despite this group of revolutionaries, the Bar at large remained loyal to the existing constitution.

The Act of Union (1800)

A significant result of the 1798 rebellion was the move by the British government to abolish the Irish Parliament, which since 1782 had legislated and governed the island of Ireland. This had a direct effect on the Irish Bar as parliament had traditionally provided a career path for barristers looking to effect change on Irish society. Between 1799 and 1800 the Act of Union was debated vigorously in the Irish House of Commons.

The barrister George Ponsonby humiliated the government ministers in numerous encounters and another lawyer, William Plunket, contemptuously dismissed the Chief Secretary, Viscount Castlereagh, as “a green and sapless twig”. The Bar even met publicly to declare its opposition to the Union. Even so, despite the excellent arguments employed, the Union was passed — thanks in part to bribery and corruption — and the Irish Parliament ceased to exist on 1 January 1801.

The Irish Bar in the Nineteenth Century

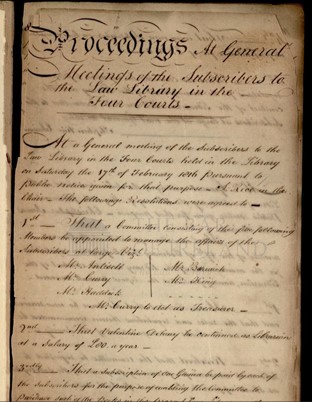

The emergence of the Law Library took place gradually over a number of years during the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th century. Without established chambers or consultation rooms barristers congregated in the Round Hall of the Four Courts plying their trade, meeting with counsel, clients and witnesses, and making themselves generally available. This was not sustainable, however, and in February 1816 at a meeting of the Irish Bar the Law Library Society was established with a view to providing a subscription-based lending library of legal texts to practising barristers. This meeting was to lead to the development of the Law Library as a distinctive feature of the Irish Bar whereby members of the Bar practised not from chambers but from a common library to which they subscribed.

Tradition has it that the Law Library evolved from a bookseller who set up on the quays outside the Four Courts and loaned books to lawyers, before moving into a smaller room within the building. The accuracy of this story cannot be confirmed but we do know that when it was established the Law Library Society came complete with subscribers, a managing committee and a librarian, Valentine Delany, who on February 24th 1816 was directed to “redeem his miscellaneous books now in pawn with so much of the amount of the debts received as will be necessary for that purpose”.

The Library Committee of the newly minted society was to precede the formation of the Bar Council by 81 years and later became the main sub-committee of the Bar under the Constitution adopted in 1914.

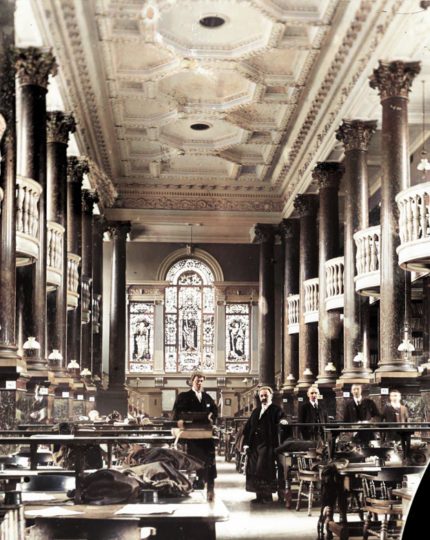

By 1832 the membership had grown to 427 and in that year a further request was submitted for improved accommodation resulting in 1838 in the completion of a new library. The environment in the new library in which barristers worked, sitting beside one another at long desks, did much to create its unique character and helped foster a sense of camaraderie. As the library grew in position as a meeting place for barristers the importance of the Hall of the Four Courts as a centre of their activity decreased massively. However, by 1840 the membership was over 600 and this new library proved inadequate with conditions unsatisfactory. In January 1880 the Law Library again, unsuccessfully, petitioned the Benchers to provide increased accommodation and better working conditions for the members of the Library.

Meetings of the Bar prior to 1897

The Law Library Committee, though informal, appears to have been a busy one, since some regular work to administer the Library must have been necessary. The ultimate authority on matters of interest to the profession, however, was a general meeting of the Bar. Many such meetings were held and were convened and chaired, at least until the end of the 19th century, by the Father of the Bar. In 1911 the Irish Law Times stated that the Father had ‘generally come to be regarded not as the member of the Bar whose call to the Outer Bar is of a date earlier than any other living barristers but as the member of the Bar who is still practising and is senior to all others so engaged in respect of his call to the Outer Bar.‘

Fees of counsel were traditionally considered at general meetings. Meetings on this subject were held in 1854 and 1864. In addition, in 1873, a meeting of the Bar resolved to establish a Barristers’ Benevolent Association which apparently foundered, since a new Association was again set up two decades later.

In 1883 the English Bar established a Bar Committee (which came to be known as the Bar Council). Sometime later that decade the Irish Bar followed suit and set up a Bar Committee which consisted of 5 ex-officio members and 24 elected members. This committee provided the driving force behind the appeals to improve the Law Library within the Four Courts. The Law Journal (London) described the conditions of the Law Library as:

close, dark, depressing, stifling in summer and freezing in winter, and it had not even the advantage of giving sufficient seating accommodation to those who wished to read or work”

(ILT & SJ Vol. 29 p. 463 21 September 1894)

A permanent or standing committee of the Bar was formed in the last decade of the 19th century. This was a natural growth from the temporary committees which had been formed on many previous occasions for particular purposes, and indeed from the arrangements which the members of the Bar had made for the administration of their Library.

Four Courts Library Act 1894

During the Christmas vacation in 1893/94, and following the establishment of the Bar Committee, an engineer examined the building and reported that it would need to:

at least double its present (cubic) capacity to provide the minimum that is generally recognized to be consistent with ordinary sanitary condition’ and that the heating system of hot water pipes should be discontinued since ‘the fireplaces with the overcrowding are sufficient to keep up a high temperature”

(ILT & SJ Vol. 28 p.43)

The conclusive argument was that the Four Courts premises was not fit for purpose. There had been a fatality among the Bar during 1894 after an outbreak of typhoid affected a number of barristers, and so eventually that same year The Four Courts Library Act provided that the Library should be enlarged and altered and general accommodation be improved. The Act stated that:

it is expedient and necessary for the purpose of promoting the health and convenience of the members of the Bar of Ireland using the Library at the Four Courts, Dublin, that such Library should be enlarged and altered and the accommodation and fittings and furnishings thereof improved”

The sum of £15,000 was given for this purpose and work was put in hand on the construction of a new Library on the southern side of the eastern courtyard of the Four Courts. It was completed in the spring of 1897 and the old Library was converted a few years later into a robing room. The work to advocate for a new Law Library which resulted in its completion in 1896 may have provided the impetus to create a formal Bar Council.

Creation of the Bar Council of Ireland 1897

Despite the indispensable role of the Law Library Society in managing the facilities of the Law Library there was an obvious need for a body to represent the Bar as a profession. Indeed, throughout the 19th century there were a number of occasions when the members of the Law Library found it necessary to come together to petition their shared interests as one voice. This reveals the steady growth in the idea of the Bar’s interests being somewhat separate to those of the King’s Inns Society and the Benchers. The Irish Times reported on 10th June 1897 that “a meeting of the Bar of Ireland was held yesterday at four o’clock in the new Bar Library.” At this meeting it was unanimously resolved ‘that this meeting declares that it is expedient that a General Council of the Bar be constituted’ (ILT & SJ Vol. 32 p. 274 (12 June 1897)).

A committee was then elected to draw up a constitution which was adopted at a further meeting a few weeks later. Henceforth the General Council of the Bar of Ireland was to be

the accredited representative of the Bar and its duties shall be to deal with all matters affecting the profession and to take such action thereon as may be deemed expedient.”

(ILT & SJ Vol. 31 p. 308 (3 July 1897))

The Twentieth Century

In the early years of the new century a change began to be felt within the political and cultural systems of Ireland. Movements such as Home Rule and the Gaelic League asserted the idea of a separate Irish identity while others made more serious plans for achieving independence by any means. The 20th century for the Irish Bar started as sedately as the 19th century had ended, but over the next one hundred years major changes in the Irish legal system would reflect the dramatic changes taking place politically. This new century would see the founding of a new state and opportunities for members of the Law Library to become influential leaders and continue to make their mark on Irish society.

The Irish Bar and the First World War

The Law Library felt the effects of the First World War at a very personal level as many barristers volunteered for service in the British forces. There were those amongst the members of the Bar who sought to play their part in what they saw as a fight for freedom and the protection of small nations. Many barristers were also graduates of TCD, where there was a very active Officer Training Corps.

When World War 1 began there were approximately 300 members of the Bar. The Irish Law Times War Supplement of 1916 numbered those called to the Bar who chose to enlist at 126 (not all of whom were practising members of the Library). In addition, the supplement also refers to 95 barristers as having one or more sons serving, a total of 160 sons of barristers enlisted. As such the Great War had a very significant and personal impact on the membership of the Bar. Of the 126 who enlisted 25 were killed in action. In 1924 a memorial by the sculptor Oliver Sheppard was commissioned by the Bar to commemorate their fallen colleagues and it can still be seen today near the entrance to the Law Library in the Four Courts. The Bar of Ireland continues to hold a remembrance ceremony at the sculpture every year on Armistice Day.

The War of Independence and Birth of a State

The failure to secure Home Rule before the outbreak of the First World War led to attempts to obtain independence through other means. The Easter Rising of 1916, which was organised by barrister Patrick Pearse, marked the beginning of a radical new phase in Irish nationalism. Though the rebellion by itself was a failure the execution of the leaders in the aftermath brought about a dramatic shift in public opinion and in the general election of 1918 the Sinn Féin party won a majority of the Irish seats.

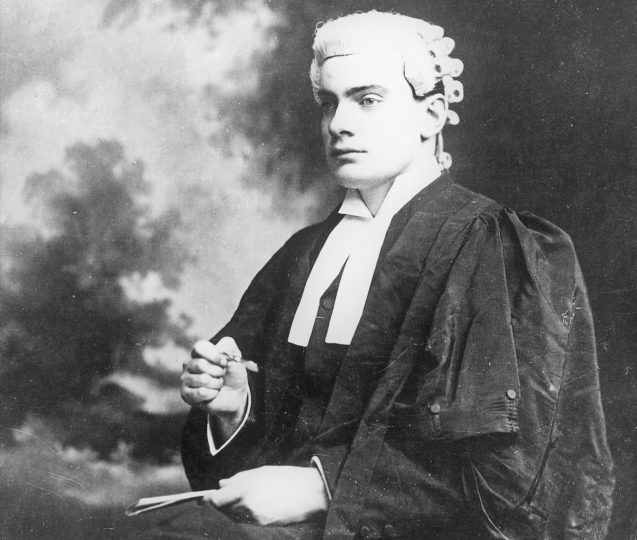

A portrait of Patrick Pearse on his call to the bar in 1901. ©Bar of Ireland Digital Archive

They refused to go to Westminster and instead set up their own parliament in Dublin – The Dáil, declaring independence from Britain in January 1919. This led to a bitter conflict, the Irish War of Independence, which ended in December 1921 with the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty that established the Irish Free State.

Partition

The Treaty had a profound effect on the Law Library and Irish barristers as the island of Ireland was now partitioned into two separate jurisdicitons. The Government of Ireland Act 1920 allowed all existing members of the Irish Bar a right of audience in the supreme courts of judicature of both Southern and Northern Ireland, effectively creating two Bars. By 1922 the Northern Bar had a fully functioning Bar Council and a Circuit of Northern Ireland. On application to the Library by members of the new Northern Bar it was agreed that the Law Library would supply copies of reports to them to help them establish a new library.

A portrait of Edward Carson. Born in Dublin and called to the Irish Bar in 1877, Carson was an influential leader of Irish Unionism in the early 20th century

In March 1922 the Library Committee considered the establishment of a reciprocal arrangement in regard to the use of dressing rooms and libraries in Dublin and Belfast by members of both Bars. It was suggested that members of either Bar could have the use of these facilities of the other for a daily fee. The committee of the Northern Bar, however, were not disposed to agree to the suggestion and they in turn proposed that members of each library could become a member of the other at a reduced subscription rate. There appears to have been no ultimate resolution of this issue as events of 1922 and beyond meant that such matters were soon forgotten about.

Women at the Bar

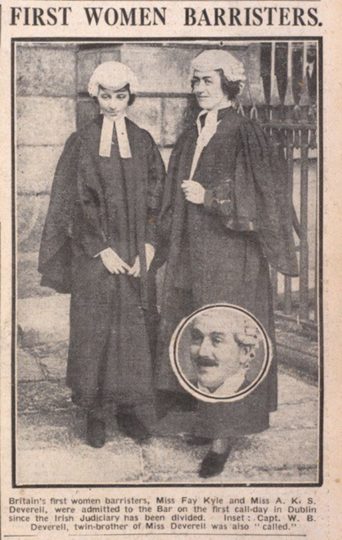

Frances Kyle (left) and Averil Deverell (right) on their call to the Bar 1st November 1921. Image courtesy of The Honorable Society of King’s Inns, from the Averil Deverell archive.

Whilst the political turmoil of the War of Independence captured the attention of Irish society a victory of a different kind was achieved with the calling to the Bar of the first two women in Ireland in November 1921. Frances Kyle became the first Irish woman to be called to the Bar on 1st November 1921 and Averil Deverell, who was called to the Bar later that same day, was the second woman called to the Bar and the first woman to practise at the Bar in Ireland.

Thus began the slow progression of women making their mark on the legal profession in Ireland.

On her first day of practice Averil Deverell arrived at the Law Library wearing the regulation wig and gown. Though in London the legal establishment referred to her wearing court dress as having “donned the horsehair with ludicrous effect” the editor of the Irish Law Times defended the circumstance by declaring “The effect is certainly far from ludicrous. It is regarded as very becoming to the lady wearer.” Thus began the slow progression of women making their mark on the legal profession in Ireland.

Destruction of the Four Courts

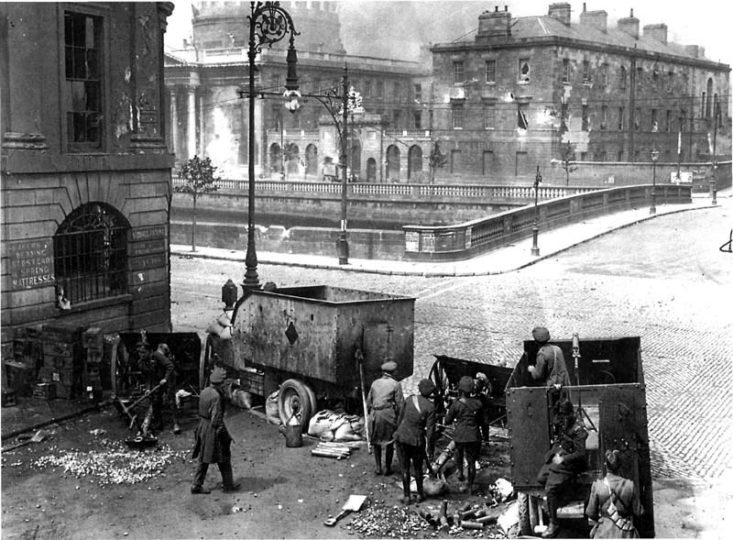

It was not long, however, before the political circumstances surrounding the achievement of Irish Independence were to encroach on the Law Library in a way never before seen in its over 100 year history. In the early hours of Good Friday, 15th April 1922, Anti-Treaty forces occupied the Four Courts building and precinct. They converted the Public Records Office into a munitions factory and mines were laid in the yards and surrounding streets. According to later accounts shortages of sandbags and barbed wire meant windows were barricaded with legal textbooks from the Law Library. Thus began a stand-off between the Anti-Treaty faction of the IRA and the Free State forces.

On 30th June a loud explosion was heard as the Public Records Office, containing seven centuries of Irish history, was destroyed.

By June 1922 the British government was repeatedly applying pressure on the fledgling state to put an end to the occupation and so the Provisional Government began shelling the Four Courts complex after a request to evacuate the precinct was ignored. On 30th June a loud explosion was heard as the Public Records Office, containing seven centuries of Irish history, was destroyed. The main Four Courts building was taken down by a second explosion, collapsing the dome and leaving the famous Round Hall, the beating heart of the barristers’ profession since 1796, in complete ruin.

An inspection of the buildings in the aftermath recorded that the Law Library was ‘completely destroyed’. As a result the Bar moved to temporary accommodations in the King’s Inns where on 14th July the Bar Council had its first meeting since April. The Bar of Ireland minute book on this day opens with the line “Owing to the destruction of the Four Courts the minutes of the last meeting were neither read nor signed as the minute book had not then been recovered”.

From temporary accommodations the Bar Council began the overwhelming process of rebuilding a library that had taken 106 years to create. The minute books tell us that “the Hon. Treasurer was authorised to pay Miss Price for typing the catalogue of the late Law Library and to pay 15/- for the hire of the typewriter”. The librarian at the time, Thomas Robbins, retired after 53 years in that position, and was replaced by Frederick Price who started the unenviable task of purchasing collections of legal texts and reports to replace those that had been lost.

From Free State to Republic

Mr. Justice Hugh Kennedy was a legal adviser to the first Dáil Éireann and the first Attorney General for the Irish Free State in 1922. He went on to become the first Chief Justice of the Irish Free State in 1924. ©Bar of Ireland Digital Archive

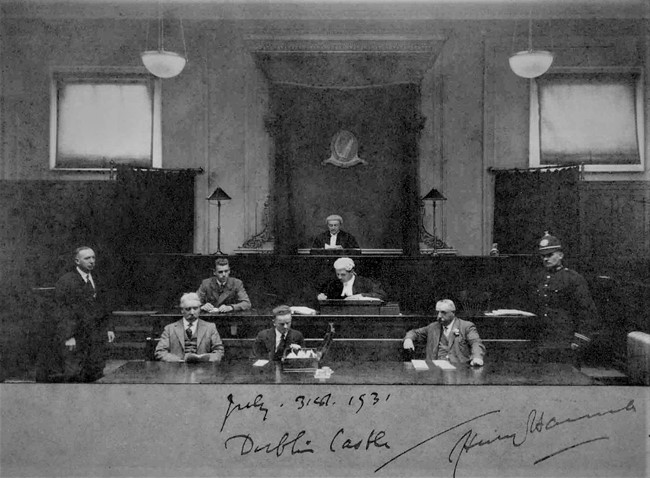

On gaining independence, the Irish Free State maintained its common law system that it had developed over the previous centuries. In 1924 the Courts of Justice Act came into force, significantly re-organising the legal system in Ireland to which the members of the Law Library now had to adjust. A new system of High Court and Supreme Court was created to replace the Supreme Court of Judicature. As well as the changes to the legal system the Irish Bar had to adapt to its new surroundings in Dublin Castle, specifically St Patrick’s Hall where they were provided with library accommodation, and where they began the process of restoring the library which had been lost in the explosion of 1922. Considerable work was undertaken in the intervening years as evidenced in August 1931 when the Library returned to the reconstructed Four Courts transferring some 10,000 volumes in the process.

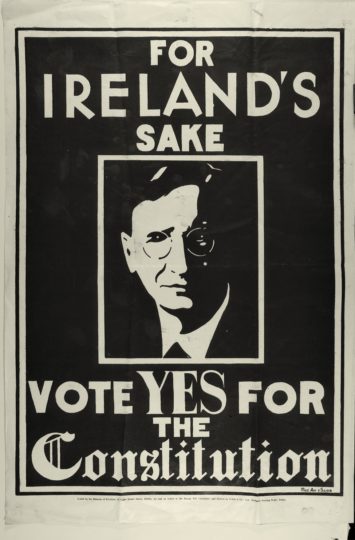

A New Constitution 1937

The next major legal change in Ireland during the 20th century was the drafting of a new Constitution in 1937. Eamon de Valera saw the Constitution as consolidating an independent approach to self-government and of removing many of the remaining unpopular links with Britain. The name of the Irish Free State was changed to Ireland, or Éire in the Irish language. This Constitution was adopted by the Irish people in a referendum on 1st July 1937, the first constitution ever adopted by popular vote.

A poster promoting a Yes vote for the new Irish Constitution, 1937. ©Bar of Ireland Digital Archive

This was followed in 1938 with the appointment of Douglas Hyde as the first President of Ireland. By 1948 the Government, led by Taoiseach John A. Costello, who was himself an active member of the Law Library when not engaged in the politics of government, had repealed the External Relations Act, formally declaring Ireland a Republic.

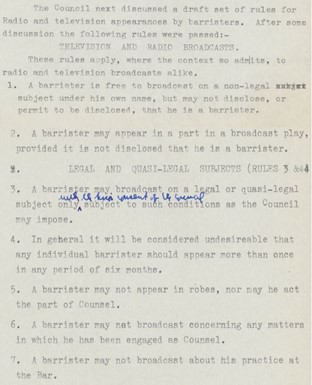

Broadcasting and the Bar

As the 20th century settled into itself, advances in the technologies around broadcasting brought more opportunities to the Bar of Ireland. With the establishment of Raidió Teilifís Éireann (RTÉ) and its developments from radio broadcasting to television, barristers in the Library were given the opportunity to showcase their expertise and provide knowledge on legal matters to the general public in Ireland in a way that was not available to them before.

Rules passed by the Bar Council in relation to television and radio broadcasts on 5th May 1967. ©Bar of Ireland Digital Archive

Initially members could only appear on the airwaves anonymously, in the minute books of 1941 we hear about Kenneth Deale BL requesting further permission from the Council to appear anonymously on Raidió Éireann after he had been involved in the radio series “Law Without Fees”. The following was the resulting ruling on the issue:

That it is permissable for a Barrister to broadcast as such on legal matters, his identity being undisclosed, provided that the matter and manner of the presentation of the broadcast are not undignified or derogatory to the profession.

By the 1960s requests for members of the Library to appear on radio and television had grown to such an extent that a set of rules for television and radio broadcasts were approved in 1967 laying out what was permissable for members of the Library when engaging in broadcasting activities.

Legal Aid and Access to Justice

The idea of legal aid as a means for all citizens to be allowed access to justice was developed throughout the 20th century and generally in line with the development of the welfare state. By the 1960s the issue of legal aid was at the forefront of legal discussion in Ireland. The Criminal Justice (Legal Aid) Act 1962 set out the provisions for the granting of legal aid in criminal cases but there were no provisions to support access to justice for those in civil cases despite the recommendations of the Pringle Report. It took the case of one woman, Josie Airey, going to the European Commission of Human Rights in Strasbourg, and represented by barrister and senator Mary Robinson, to highlight the issue. The Commission found that Ireland was in breach of Article 6 of the Convention on Human Rights and the right to a fair and public hearing. The success of Mrs. Aireys case led to the establishment of the Legal Aid Board in 1979 and the development of a civil legal aid scheme which was placed on a statutory footing by the Civil Legal Aid Act 1995.

FLAC – Free Legal Advice Centre

As a profession, the Bar has a long tradition of protecting and advancing the interests of less well-off members of society. FLAC (Free Legal Advice Centres) was founded by four law students looking to use their legal knowledge and provide advice and information to those who could not afford the fees involved. David Byrne, Denis McCullough, Vivian Lavan and Ian Candy set up the organisation in April 1969 after attending a conference on Legal Aid in Trinity College Dublin. The group’s ultimate objective was to influence national government into instituting a more comprehensive plan that afforded civil legal aid for those who needed it. In the interim the group started to provide legal representation, advice and information to the public.

Over time FLAC has become involved in a wide range of social issues, with a particular focus on social welfare, but also on credit and debt law, immigration law and equality. Many members of the Law Library have joined over the years giving advice to those who can’t afford it both as law students and as they progressed through their own careers. It celebrated its 50th anniversary in 2019.

The European Union and New Opportunities

In 1973 Ireland formally joined the European Economic Community, now known as the European Union. Our membership was to have wide reaching effects on Irish society, not least within the legal sphere, as new laws on discrimination, protecting workers’ rights and equality came into force throughout the 1970’s. New opportunities for advocacy work in the European Court of Justice were opened up and later provision was made for practitioners from one jurisdiction to practice in another within the Union. A number of former members of the Law Library have also gone on to sit on the European Court of Justice.

There were new political opportunities for members of the Law Library, where the tradition of barristers taking up political office goes back over 200 years. Since 1973 four of the Irish Commissioners sent to the European Commission have been barristers: Richard Burke, Michael O’Kennedy, Peter Sutherland and David Byrne.

The Irish Bar Today

The Bar in Ireland has changed considerably in the over 200 years of the Law Library’s history. In the 21st century the Bar continues to play a major role in the life of the Irish State. Barristers pursue justice in the Irish courts and protect and guard the rights of every citizen whilst adapting to changes in the provision of legal services in line with technological developments.

Through all of these changes, and at their heart, has been the Law Library. From humble beginnings in a corner of the Four Courts to a membership of over 2,000 barristers across four locations, the Law Library has supported the independent legal practice of so many of its members by providing the space where they can grow their expertise. This in turn has allowed countless barristers over the centuries to create the unique environment of collegiality we see today.