It is rare to see the Supreme Court fully flex its considerable judicial brawn in sweeping away a long-established legal principle. When what is swept away is as familiar and foundational a principle to employment lawyers as the mutuality of obligation, the sight is all the more impressive.

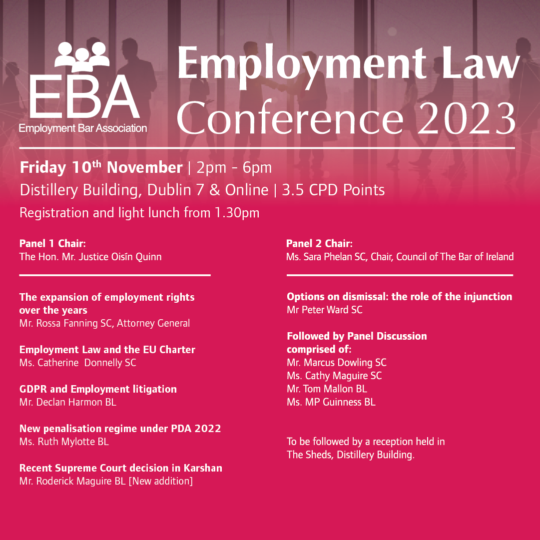

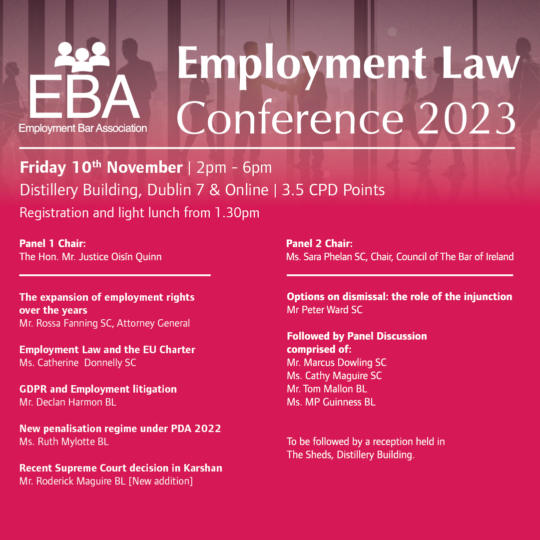

In advance of the forthcoming Employment Bar Association Annual Conference, Kevin Bell BL examines the outcome of the recent Karshan v Revenue Commissioners case determining the status of pizza delivery workers as employees rather than contractors, including the ramifications for employers and what it means for the gig economy.

Determining a Contract of Employment

The principle of the mutuality of obligation has been described as a sine qua non of the employment relationship, and an important filter in determining whether a contract of employment exists in a particular context. In the 14 years since its first appearance in Ireland in the judgment of Edwards J. in Minister for Agriculture v. Barry [2009] 2 IR 215, the courts and adjudicating bodies had developed the principle to require an ongoing relationship between the contracting parties. This relationship required a future-oriented commitment on the part of the employer to provide work on an ongoing basis, and a corresponding duty on the part of the employee to perform that work. The authors of Employment Law in Ireland neatly summarised this ‘Continuity Approach’ in the following terms:

“In this scenario, mutuality of obligation is not only relevant to the formation of the contract; it also demands an ongoing commitment by the employer to provide work and the employee to do it. That is to say, mutuality also refers to a ‘second tier of obligation’ consisting of mutual promise of future performance’. As McGaughey explains, to satisfy this form of mutuality of obligation the ‘employer had to have accepted an ongoing duty to offer work, and the staff an ongoing duty to accept it.”[1]

It is in this context that the long running litigation in Karshan (Midlands) Limited t/a as Domino’s Pizza v. Revenue Commissioners [2022] IECA 124 arose. In 2014 the Revenue Commissioners determined that pizza delivery drivers engaged by Domino’s as independent contractors were in fact working as employees, and as a result Domino’s were deemed liable for PAYE and PRSI contributions in respect of those drivers.

As is the case in most of the arrangements between companies and gig workers, Domino’s contracts with its drivers described the latter as independent contractors. The contracts stipulated that the drivers were to be paid according to the number of deliveries successfully undertaken and for marketing the company via promotional uniforms and advertising.

Domino Domino’s?

Domino’s contended that the Revenue Appeals Commissioner erred in law in her interpretation and application of several issues when determining that the drivers were engaged pursuant to contracts of service, including in her interpretation of the mutuality of obligation

The High Court, on appeal, held that the written contract between the appellant and respondent contained the requisite mutuality of obligation to constitute a contract of service, and that it was not necessary in order to establish mutuality of obligation that an employer was obliged to provide work on an ongoing basis.

In a majority decision, the Court of Appeal found in favour of the appellant and overturned the High Court decision. Costello J., for the majority, ruled that the High Court had erred in determining that there was no requirement for ongoing obligations to provide and carry out work, in order for the mutuality of obligation to be fulfilled.

Murray J. – for a unanimous Supreme Court – witheringly commented that the phrase “mutuality of obligation” had been transformed “through a combination of over-use and under-analysis” into something it was never intended to be. From an analysis of the foundational jurisprudence, in particular Ready Mixed Concrete (South East) Ltd. v. Minister for Pensions and National Insurance [1968] 2 QB 497, Murray J. determined that the more minimal interpretation of mutuality advanced by the High Court was the correct one.

Mutuality of obligation, the court held, means no more than the ‘wage/work bargain’ that is satisfied when a worker agrees to undertake a particular item of work in return for pay. It requires no ongoing relationship, or any future commitment to provide or perform work.

In sweeping away the established ‘Continuity Approach’ to mutuality of obligation, the Supreme Court has fundamentally altered the basic conception of the employment relationship in this jurisdiction.

5 Tests to Determine Employment Status

In its place the Court offered the following five-stage test for assessing whether an employment contract exists:

- Does the contract involve the exchange of wages or other remuneration for work (that is, does it satisfy the new understanding of the mutuality of obligation)?

- If so, is the agreement one pursuant to which the worker is agreeing to provide their own services, and not those of a third party, to the employer?

- If so, does the employer exercise sufficient control over the worker to render the agreement one that is capable of being an employment agreement?

- If these three requirements are met, are the terms of the contract consistent with a contract of employment, or are they more consistent with the worker being in business on his own account?

- Is there anything in the particular legislative regime under consideration that requires the court to adjust or supplement any of the foregoing tests?

Adapting to a Modern Context: Gig Economy

The Domino’s workers, whose employment was at issue in the proceedings, were emblematic of a new, and distinctly 21st Century phenomenon: the gig worker. Their precarious position within the economy, and the harshness which the application of the pre-existing definition of the employment relationship entailed for their circumstances, may have justifiably played an unspoken part in the court’s consideration of their status.

The strength of the common law (and mutuality of obligation is a quintessential common law principle) is its ability to adapt, whilst maintaining continuity with the established principles of the past. The Supreme Court’s new definition of mutuality of obligation represents a bright-line adaptation of Irish common law, albeit in the specific context of a tax case.

The development of the law in this way will have far-reaching ramifications for employers, and for the gig economy. It remains to be seen whether the business models of gig employers prove to be as flexible as the principles of the common law.

[1] Employment Law in Ireland, Cox Corbett & Connaughton, 2nd. Ed., Clarus Press, para.2-66

The views expressed above are the author’s own and do not reflect the views of The Bar of Ireland.

Discover the Employment Bar Association

The Employment Bar Association (EBA), supported by The Bar of Ireland, is an association of Senior and Junior Counsel who practice in, or have an interest in, those areas of law.

We specialise in employment, equality and labour law in litigation and in advising and supporting employers and employees in resolving workplace disputes.

We are Lawyers, Litigators and Certified Mediators who specialise in employment and workplace law. We also conduct Workplace Investigations, draft Legal Opinions on workplace employment law questions and advise and negotiate for employers and employees.